Food, Water, and Shelter: Basic Needs in the West Bank Under Threat of Settler Violence

Part Two: Water Insecurity in The West Bank

In the arid village of Al Auja, about 10 miles outside of Jericho, water and daily access to it dictates one’s way of life. Water is the most crucial resource for those in the village, and access to Ras al Ein, the only remaining natural spring on Palestinian land in the locality, serves as the only means by which to make the arid climate inhabitable. This dire reality is not just a lived experience for the villagers of Al Auja — it is also well-known by settlers in the area who wish to push Palestinians out.

Not far from the Palestinian city of Hebron, in the rolling hills of Masafer Yatta, lies the ancient Palestinian village of Susya. Not unlike those in Al Auja, the residents of Susya face issues of water shortage and scarcity, especially during the dry seasons. The Masafer Yatta region receives 80-100 mm of rainwater annually, or about 600 mm less than the Jordan Valley area.

This shortage creates a reliance on groundwater and a strict adherence to storing any rainwater that may come during the wet seasons. Even with dutiful storage of all supplemental rainwater, villagers may still find their ground wells dry by the mid to late summer months. Given that storing rainwater and relying on ground wells is crucial to the agricultural and day to day needs of Palestinians in Masafer Yatta, the demolition and destruction of water tanks and wells is the most common approach to undermining water supply in the region.

In both cases — which are far from outliers in the West Bank — the common thread is attacks on water infrastructure by Israeli settlers.

Attacking the water supply is a common tactic among settlers who seek to forcibly remove Palestinians from their villages. By directly attacking basic needs like water which villagers rely on for drinking, bathing, agriculture, and livestock, settlers are able to undermine this life-giving resource with relative ease. Whether it’s by threatening death or bodily harm while accessing natural springs in the north, or destroying rainwater reserves and wells in the south, the result is the same for Palestinians. Restrict the amount of water available to a population, and mass migration or death will surely follow.

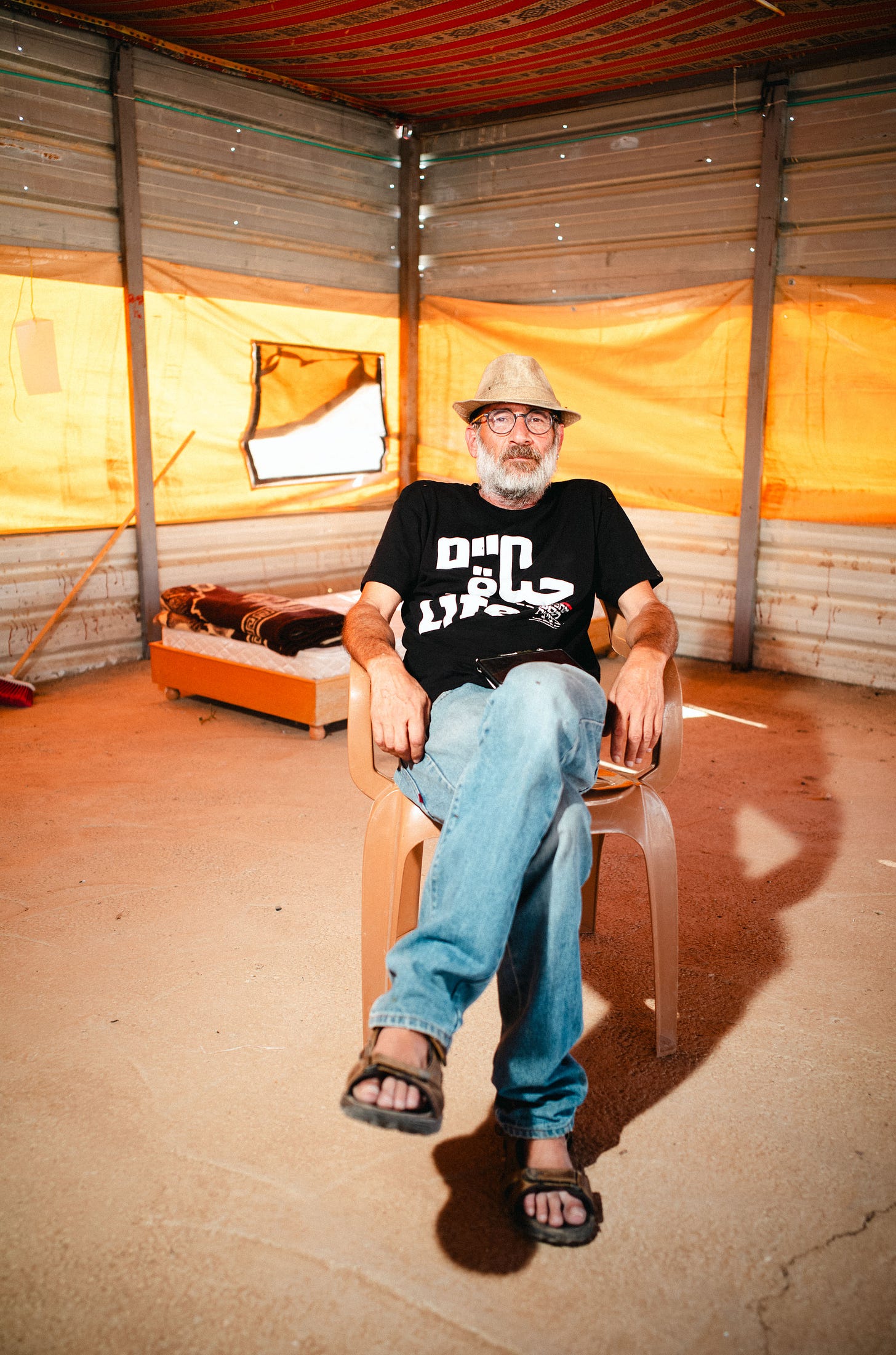

During my time in Al Auja, I interviewed Guy Hirschfeld, a lifelong Israeli activist in the Jordan Valley area, about some of the ways in which water is both used by and restricted from Palestinians. Hirshfeld runs an activist movement called Looking the Occupation in the Eye which focuses its efforts on picketing near Israeli checkpoints in the West Bank and offering protective presence for villagers in Al Auja who seek to access Ras al Ein, the natural ground spring that supplies the surrounding area with fresh water.

While driving past Israeli settlements featuring bright green, sprawling palm tree farms, I asked Guy about the amount of water needed to operate one of these farms.

Brendan: “Can you talk about the agricultural needs in the Jordan Valley area, particularly the amount of water necessary to maintain these farms?”

Guy: “The agriculture is […] first of all, everything behind the fences is Jewish agriculture. Now we are in the center of the Jordan Valley, all of these lands [which the settlements are located on] were taken in the 70s.”

The land seizure he is talking about came after the Six-Day War in 1967. The land in question — particularly 15.5% of Al Auja — is designated Area A, meaning in theory that it is under full control of the Palestinian Authority. Agricultural settlements, like those we drive past, popped up in the area during the early 2000s and require large amounts of water which is often sourced from Palestinian ground springs in the area.

G: “Traditionally, trees like this would rely on the supply of ground water in the Jordan Valley, [but these] date trees […] palm trees get something like 600 liters of water per day.”

Trees like the date palm were in fact native to the land. But since the early 2000s, their cultivation experienced a vast uptick in popularity in the Jordan Valley region and the farming techniques used to supply dates to Israeli and global markets reflected practices that were anything but native. Date trees harvested by Israeli settlers can use anywhere from 700 to 1000 liters of water per tree per day during the ripening period. Water which would have historically — or ‘traditionally’ as Guy prefers to put it — been pulled from the ground naturally by trees. Now settlers rely on two primary sources to quench millions of water-hungry trees: wastewater transported from Jerusalem, or water from natural springs. The latter of which is primarily owned by Palestinians living in Area A.

Shem Tov is one of many violent settlers in Susya who uses intimidation tactics, threats, and property damage to undermine water security in the village. On August 4, 2024, Tov threatened B’Tselem reporters with, “Rape in the name of God.” After threatening to take over a Palestinian home — claiming he built the home and dug the well — Shem Tov chided, “You know Sde Tieman? Sde Tieman?”, an Israeli detention center, which faced internal and international investigations after video of soldiers raping Palestinian political prisoners was leaked to the press.

In Al Auja, on August 8, 2024, while following Guy Hirshfeld for a routine check up on Palestinians near Ras al Ein, our car was surrounded by intoxicated settlers who were using the ground spring as a personal bathhouse. Below is a version of the video which features a brief follow-up explanation of the settlers’ behavior offered by Hirshfeld. (©Brendan F. Rains)

Later that day, after video from Hirshfeld’s dash cam was send to military and police in the area, the settlers were asked to leave the Palestinian ground spring. The military order to vacate property that did not belong to them resulted in the destruction of a Palestinian man’s automobile which was parked about 400 meters downstream of the spring. When I spoke with the owner of the car, he described drunken settlers, some in their underwear, approached him and began damaging his car by kicking it, throwing rocks, and hitting it with sticks. Inside of the front passenger seat, a bottle of beer similar to those from video earlier in the afternoon, can be seen.

In Al Auja on August 17, 2024, Russian-born human rights activist, Andrey X, was lured away from the natural spring, Ras al Ein, where he was offering protective presence to Palestinians accessing water. The two settlers, who staged a situation in order to draw Andrey and other activists away from the water source, struck him on the head and legs with a stick. The altercation resulted in the rupturing of his eardrum.

Activists like Guy Hirshfeld and Andrey X certainly believe that presence of international activists is the best route to stopping water apartheid enacted through settler violence; they put their own security on the line to back that belief up.

But going forward, legal framework will be required to ensure continued Palestinian access to water. Some Palestinians believe in the prospect of American sanctions or UN intervention against settlements. Others remain hopeless over the continuous expansion of Israeli settlement farmlands and infringement on their water supply to quench crops like mangoes, intended to be grown in tropical climates.

With agricultural settlements like the Einot Kedem Farm — which maintains tens of thousands of water hungry crops and invites American donations to participate in “settling the land, cultivate wilderness, and be a pioneer" — being built only kilometers away from Palestinian villages, the task of protecting Palestinian access to water may be a tall order.

While each case of settler violence against Palestinians varies and the degree to which justice is or is not doled out is case by case, one factor remains constant: each act of settler violence is an affront to Palestinian food, water, and shelter — the very foundation of survival.

NOTE TO READERS: This Substack is part two of a three part series titled Food, Water, and Shelter: Basic Needs in the West Bank Under Threat of Settler Violence.